Knowing oneself intimately, in part through a practice of critical reflection – independently as participant in dialogic exercises with those whom you share a history and a worldview – is integral to becoming a socially responsible scholar, activist, or teacher. This is a challenge we must pose to ourselves, as we embark upon our roles as educational leaders; regularizing reflexivity may make us more aware of our roles as learners ourselves, and our immense obligation to our students and our institutions to participate in a culture of excellence, providing all students with equitable access to fruitful learning experiences. Parallels between the important messages of Aurora Levins Morales in Medicine Stories (1999) and Tyrone Howard’s “Culturally Relevant for Critical Teacher Pedagogy: Ingredients Reflection” (2003) emerge around one’s own identity and the relationships one has with content and their context, including the fabrication of “the other.” The experiences, cultural traditions, positionality in terms of power and the socio-economic landscape, and education are part of what make up one’s identity. These factors also cultivate the perspective, including judgments, biases, and imaginings, one carries with him/her. Critical reflection is a “personal and challenging” process of looking at “one’s identity as an individual person and as an active professional” (Howard, p. 201), and that “gives attention to one’s experiences and behaviors, [wherein] meanings are made and interpreted from them to inform future decision-making” (p. 197).

My professional agenda involves developing a college preparatory independent learning program, delivered online, for grades 7-12. It is precisely the broad acknowledgement that each individual student has his/her own context, impacting his/her learning needs, preferences, and abilities that led to this endeavor. The new charter school is a part of the Arizona Online Instruction Program, and will attempt to support each student to clarify goals, connect academic expectations to nonacademic interests, and creatively pursue aspirations within the flexible program structure. I recently engaged in research on online learner characteristics, which proposed that certain characteristics seem to lend to greater success in online education settings (or, that the absence of these characteristics may require more substantial or targeted support and intervention strategies). This work helped me think about how I would build a program that understood and was designed to adapt to each student’s characteristics/context from the moment of our first meeting. The combined works of Morales (1999), Howard (2003), Garcia and Ortiz (2013), and Gould (1996) have helped me see the immense value of my participating in the exploration of [my own] personal characteristics and how they may impact my performance as mentor, program advisor, parent counselor, facilitator, and administrator.

Howard quotes Palmer (1998) who wrote that “we teach who we are,” and “knowing myself is as crucial to good teaching as knowing my students and my subject” (Howard, p. 198). It may be that our positionality enables a blindness to our beliefs and the behaviors that stem from them. Teaching is not a neutral act (Howard, p. 200), neither is storytelling (Morales, p. 25). Morales encourages us – scholars, teachers, socially-responsible citizens of the global society – to make ourselves visible (to ourselves, in our writing, in verbal our story telling), as she has chosen to do. This, in and of itself, is an act of resistance against the dominant approach – the imperial history is one where the narrator is detached, and makes no explicit moral judgment, or demonstration of partisanship, though, this story is an unabashed construction of the oppressors. For Morales, the work of the “oppressed” or the underprivileged breaking silence and voicing memories, experiences, including and especially about trauma, offers a pathway for collective healing, empowerment, and a way to restore our sense of humanity. The author advocates for the crafting of “medicinal histories” which “seek to re-establish the connections between peoples and their histories, to reveal mechanisms of power, the steps by which their current condition of oppression was achieved through a series of decisions made by real people to dispossess them; but also to reveal multiplicity, creativity and persistence of resistance among the oppressed” (Morales, p. 24).

Morales’s “handbook” for medicinal histories recommends similar actions as Howard, the broad purpose for both seems to be to enhance the access to personal and collective narratives not born entirely from the dominant narrative, and enhance equitable access to quality education and to achievement, not entirely fraught with invisible devices of the privileged, that unconsciously or consciously deploy to impact learning opportunities and outcomes. Morales urges the inclusion of nonwritten, and, for lack of a better characterization, nonobvious or mainstream media or sources of “evidence.” By this she does not mean fabricating data to report it as science (which might invite the reader to recall the example of craniometry, which was hailed as scientifically justifiable in the nineteenth century (Gould, 1996)); rather, the objective is to offer a space or an ear to the voice of the silenced, which may yield a yet untold story or perspective. She encourages proposing questions as an important investigatory tool, even very broad-based or seemingly unanswerable ones, as they can lead you in directions perhaps underrepresented in the dominant narratives. The author contends that we perpetuate injustice by not revealing power dynamics and by not revealing the agency and the “real people” among the oppressed; the new narrative must be as complex as the reality it tells, embedded within and expressing connections from its context.

Then, it is up to the story teller to further make meaningful the narrative through careful choice of language and approach, and an understanding of the contexts within the audience – much like a teacher. By not making accessible, which for Morales involves the actual “delivery,” or digestibility (p. 36) of the story, the narrator has effectively excluded some. Sharing stories and working to understand each other’s contexts may help denigrate the myth of the monolithic oppressed or “unprivileged” class, reducing cultural variations, and rendering insignificant major differences within groups – including within one classroom. As Garcia and Ortiz (2013) point out, “a master category like race/ethnicity fails to account for within-group diversity based on people’s multiple social identities” (p. 36), which, in the context of teachers and students, can have real impact on how educational institutions address the particular learning styles and needs of individuals. Much as “ecology undermines ownership” (Morales, p. 100), because it is inherently full of highly variant, dynamic, and interrelated components, whole groups of people, irrespective of their commonalities, cannot fairly be referred to as a unit devoid of internal contradictions, inconsistencies, and uniqueness.

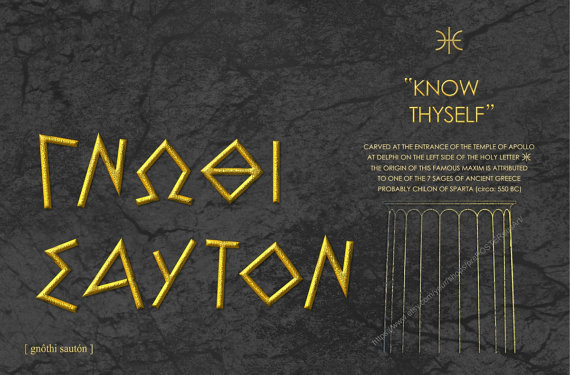

Howard is concerned particularly with deficit-based characterizations of non-dominant or culturally diverse students, suggesting that this may lead to the reification of these individuals as better suited for special or remedial education or even directly impact their achievement. Culturally relevant pedagogy may well be a way to help “increase the academic achievement of culturally diverse students;” it “uses ‘the cultural knowledge, prior experiences, frames of reference, and performance styles of ethnically diverse students to make learning more relevant to and effective [for students]. …It teaches to and through strengths of these students. It is culturally validating and affirming” (p. 196). Strategic critical reflection among teachers, facilitated by skillful and open teacher-educators is the neverending process that can engender culturally relevant pedagogy. It must be guided by specific questions or foci, e.g. “Who am I? What do I believe? Does who I am and what I believe have ramifications for the students I teach?” (p. 199), the musings on which inform one’s behavioral modifications.

It is through purposeful critical self-reflection, along with iterative, reflexive, behavior change that we may be able to push back against the status quo to strive for excellence in our educational institutions, providing an environment better suited for all students to feel comfortable and to participate fully in the learning experience toward individual academic success. At the very least, we can use this as a tool to interrogate that which guides our own behavior and the potential impact it has on those around us, particularly our students, and remind us that part of our identity is as active participants in the context within which we engage with our students and our schools. Sounding the rallying cry of a sustainability scholar (which appeals particularly to me, having done my graduate work in sustainability), Morales writes that “the denial of our interrelatedness is killing the planet and too many of its people” (p. 14). It is not just to the detriment of our ecosystem that we ignore the interconnectedness of all things, it is a social justice issue and truism that can guide teacher critical reflection. Because of this role and our individual and collective desire to have a(n) [evermore] positive impact on our students’ intellectual pursuits and lives more generally, we have a responsibility to make visible the invisible, including things about ourselves, from where we came, our positions [of privilege], and interrogate and take action on how they affect our outlook and approach.

Garcia, Shernaz B.; Ortiz, A. A. (2013). Intersectionality as a framework for transformative research in special education. Multiple Voices for Ethnically Diverse Exceptional Learners, 13(2), 32–47.

Gould, S. J. (1996). The mismeasure of man. In The Mismeasure of Man (p. 444). Norton.

Howard, T. C. (2003). Culturally relevant pedagogy: ingredients for critical teacher reflection. Theory into Practice, 42(3), 195–202.

Morales, A. L. (1999). Medicine stories: History, culture and the politics of integrity (p. 135). South End Press.