“I was a listening child, careful to hear the very different sounds of Spanish and English. Wide-eyed with hearing, I’d listen to sounds more than words. First, there were English (gringo) sounds. So many words were still unknown that when the butcher or the lady at the drugstore said something to me, exotic polysyllabic sounds would bloom in the midst of their sentences. Often, the speech of people in public seemed to me very loud, booming with confidence. The man behind the counter would literally ask, ‘What can I do for you?” But by being so firm and so clear, the sound of his voice said that he was a gringo; he belonged in public society” (Rodriguez, 1982, p. 2)

One of the first reading assignments I give my sophomores each year is the essay “Aria” by Richard Rodriguez. I like this essay for lots of reasons–for one, my course emphasizes literary nonfiction and the personal essay, as I feel that these are understudied modes of composition for most high-schoolers. I also like this essay because it initiates my students and orients them to some of the meaty subject matter we’re going to tackle over the course of the year: marginalization; the phenomenon of the Other; the way language can be a signifier of power and privilege, a way to let people in or a way to make sure people stay out; multiple intelligences and definitions of success; and the multilayered nature of identity–the way we constantly renegotiate and navigate identity as we learn more about ourselves and the communities to which we belong (or don’t).

We read, among other things, The Namesake, by Jhumpa Lahiri, and Best Intentions: The Education and Killing of Edmund Perry. These two books, one longform literary fiction and the other longform literary nonfiction, both feature “characters” who struggle to navigate split identities. In The Namesake, Gogol Ganguli is an Indian-American growing up in the Northeast of the US, plagued by the confusing feelings of embarrassment and pride, belonging and not-belonging, presented by his immigrant parents and his American surroundings. Best Intentions tells the story of Edmund Perry, a smart, hardworking, promising black student from Harlem who attends the prestigious Philips Exeter Academy. There, he racks up good grades and accolades but he intermittently charms and confuses his peers and faculty: is he the great hope of the slums, a city boy done good? Or is he a threatening and aggressive black man? It does not escape my students’ notice that these polarized and reductive identities seem to be the only ones on offer to Eddie. Tragically, the summer after he finishes at Exeter, before heading off to Stanford on a scholarship, he is shot and killed while attempting to assault an undercover cop back in Harlem. As the title suggests, the book examines not just the circumstances of Eddie’s death but also his attempts to straddle, negotiate, and reconcile two worlds, two identities.

Many of my students are navigating that very space, and as sophomores they are (newly) able to examine that experience and discuss it intellectually, critically, honestly, articulately. So I kick them off with the Rodriguez essay because I know it will resonate deeply and personally with many of my students. Some of my students learned English as a second language, and even among those who learned English first, many learned another language concurrently: Spanish, Hindi, Bengali, and Mandarin, mostly. And so language becomes a great way for us to talk about the many communities a person can belong to, and the way that membership in one community–school, for example–can sometimes mean feeling like you have to sideline, ignore, or deny your membership in another. All year long we talk about what it is like to live in the margins.

My school is a secular independent school. It costs, well, a lot of money to go there. A year’s tuition costs more than I made at my first job out of graduate school. Most of my students are white, upper middle-class, and affluent. Another good proportion are not white (many of Indian descent, many Asian, several Hispanic, and very few Black), upper middle class, and affluent. And about a quarter are working class, decidedly not affluent. Most of those students are Hispanic, a few are white, and very few are Black.

Several of my students come to my school by way of an outreach program, the mission of which is to “to enrich, engage, and empower first-generation college-bound students from local public schools and partnering organizations, their educators, and their parents by providing resources, academic enrichment, and opportunities that encourage intellectual, cultural, and personal growth” (“Project Excellence”). The mission of the program is two-pronged. It offers a student program, which “provides necessary resources and opportunities that most first-generation college-bound students do not have access to during the regular school day. The Program consists of weekend workshops, a robust summer program, and a variety of mentor opportunities” (Project Excellence). There is also an adult program, which “provides adults in the greater Phoenix community with educational enrichment opportunities through weekend and summer workshops in English Language Learning (ELL) and General Education Coursework (GEC), with the expectation that enriching the lives of adults has a direct, positive impact on the lives of children of the community” (Project Excellence). I believe in the mission of this program and participating in its summer and weekend workshops, which are extended to students who don’t attend our school as well as the ones who gain admission as “scholars,” matters to me. I feel sheepish that as I’ve gotten busier and responsible for more things at school in the six years I’ve worked there, my own participation in this worthwhile outreach program has dissolved.

Nevertheless, regardless of our level of participation in outreach workshops, we faculty say–and, I think, genuinely believe–that these students are in no way provisional, less capable, or less college-bound than their classmates. Certainly our college counselors would never say, “Look, I need my car mechanic and if everyone goes to college, then where am I going to get my mechanic” like the (admittedly) strained and over-tasked career counselor at University High School, a sprawling comprehensive public private school studied in “Unveiling the Promise of Community Cultural Wealth to Sustaining Latina/o Students’ College-Going Information Networks” (Liou et al., 2009). I think if you asked any of my co-faculty if they treat these students any differently than their peers, they’d say no.

We have high expectations for all of our students. There’s not a second-tier track. But to treat these students the same as their peers seems unfair, when many of them have jobs outside of school; extensive religious commitments; responsibilities to provide child care for siblings; less practice with reading and writing (especially in the formal language of school); less familiarity with academic navigation (seeing this counselor, turning in that form, etc.); less access to Internet resources at homes and fewer computers, phones and devices; atrophied or underdeveloped study skills; less access to expensive tutoring or test-prep opportunities; or parents who, because of language limitations or job commitments or both, can’t advocate them the way their peers’ parents can.

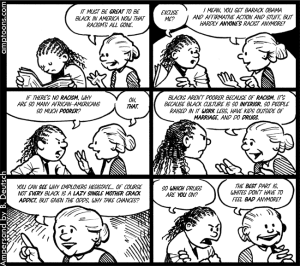

And so, because we teachers want to make ourselves aware of the backgrounds these students come from and help them succeed, we may unintentionally operate on a cultural deficit model, which posits that “the student who fails in school does so because of internal deficits or deficiencies. Such deficits manifest, it is alleged, in limited intellectual abilities, linguistic shortcomings, lack of motivation to learn, and immoral behavior” (Valencia, 2009, xi). I would not be the first to point out that for many people who operate on the deficit model, race or economic class alone presents the deficits. People take a nugget of research they’ve overheard–that, say,”in poor and working-class households, children were urged to stay quiet and show deference to adult authority figures such as teachers” (Goldstein, 2014) whereas middle-class students learn to self-advocate or “white parents are at least twice as likely as black and Latino parents to request a specific teacher” (Goldstein, 2014)–and run with it. Next thing you know, even the most warm-hearted, well-intentioned, politically liberal and dedicated teachers are standing around in the faculty lounge saying, “Well, you know, these students just don’t know how to do what you’re asking them to do. Coming in for extra help, staying for office hours, completing extra credit assignments, this is not part of their world. It’s not what they do.” But it’s a dangerous pendulum–swing too far toward “treating everyone the same” out of some well-intentioned idea of educational equity and colorblindness, and you don’t help these students succeed.

Either way, from the deficit perspective or the everyone’s-treated-the-same model, you leave these student to figure it out on their own; you push responsibility for their success back on them and their families; you make academic success a thing to be attained by individual, entrepreneurial pluck, just as in “Keeping Up the Good Fight: the Said and Unsaid in Flores v. Arizona” the authors argue that neo-liberal values render language “left to the competitive market, where individuals and groups have to battle with each other for access” (Thomas et al., 2014, p. 250). You hope that they can leverage their other kinds of capital (aspirational, linguistic, social, navigational, familial, resistance) (Liou et al., 2009, p. 538) to succeed–not because of you, but despite you.

The school where I teach is not facing the problems that large, comprehensive public high schools in economically depressed cities are facing. Still, the independent school realm has its own issues to confront regarding race, equity, and diversity. One of the movies my students and I watch together during their sophomore year is “American Promise,” a documentary that follows two black New York City students as they embark on schooling at the prestigious–and nearly all-white–Dalton School. In the film, a Dalton administrator theorizes that independent school culture presents “a greater cultural disconnect for African-American boys” (Ohikuare, 2013) than for black girls. In fact, both of the boys profiled in the film struggle with their Otherness, and one of them ultimately leaves to attend the nearly all-Black Benjamin Banneker Academy, finding more happiness and success there. We watch this movie in tandem with reading Best Intentions, and while my students are pondering what it is or might be like to feel so alien in such a pressure-cooker environment, I’m wondering if my fellow teachers and I are doing right by the students of color that are sitting in my classroom that very minute.

I have seen my students leverage the kinds of capital that Liou et al. describe as the saving grace of students whose schools and counselors are failing them, keeping college-going know-how a closely guarded secret, etiher out of the deficit-model belief that they’re not going anywhere anyway or out of the more sinister desire to preserve a (brown) servant class to fix their cars.

Certainly my students have aspirational capital, “the ability to have high hopes for the future in spite of social, economic, and institutional barriers” (Liou et al., 2009, 538), as do their parents, or they wouldn’t have applied to our school, taken the battery of admissions tests, or ridden three buses every morning to get there. They have impressive linguistic capital, which allows many of them to succeed by traditional measures–acing AP Spanish, for example–and to write compelling and vivid poetry or prose that is colored by diverse linguistic influences and words and which is well-received and celebrated by their classmates and teachers in student publications. They have social capital, loving “networks of people and community resources,” and they “draw instrumental and social support through sources such as community based organizations, churches, and community-based cultural and athletic events” (Liou et al., 2009, 538). Many of them have active church or athletic lives that bring them in contact with students from other schools and communities. Through these experiences, many of them hear reinforcement of what they’re hearing at school–register for that PSAT!–but they’re hearing it from people like them, people who can empathize with them even if most of their classmates cannot. They have impressive familial capital. Many of them report studying with older siblings, aunts and uncles, or cousins when parents can’t help because of linguistic barriers. These opportunities and connections allow them to leverage their navigational capital. And, to some extent, I’ve seen “resistance capital,” or “those skills that are garnered through oppositional identities/behavior that challenge instances of inequality” (Liou et al., 2009, 538).

I’m thinking particularly of a former student, D.G., who, though reticent at the beginning of the year, gradually found powerful material to write and speak about in my class from comparing her own experiences with those of her more comfortable, coddled classmates. D.G. derived great strength, worldliness, and an identity as a no-nonsense survivor from her glimpses into the values and experiences of her rich classmates who couldn’t code-switch the way she could, who didn’t know what it felt like to get a paycheck, and didn’t ever have to fight to get what she needed from a school or teacher, never had to demand that they be treated the way they deserved to be. D.G. absolutely found a way to leverage “marginalization as a motivation concept” (Liou et al., 2009, 546). One time, her classmates were all fawning over a student, a girl, who had come to class with an impressive black eye from that morning’s pre-school karate practice. D.G. sat back, arms crossed, and surveyed the room with a sour expression. She sat apart. As the girls oohed and aahed over the shiner, one of them said, “Oh, I want a black eye!” Quietly, smirking, D.G. uttered, “I could help you with that.” Laughs all around. As a teacher, or course, responsible for the safety of all my students, I cringed. But part of me cheered for D.G.’s finding strength and humor in the stark contrast between her lived experiences and those of her classmates. Over time, D.G. found a balance between the tough aspects of her identity and the more vulnerable. She’s now a college freshman studying public health. Recently, she came back to visit and explained this choice of major, a departure from the pre-med major she’d planned on. She said she wanted to work with people, and this way she could help people who are underserved by the system the way it is. “You want to fight the good fight?” I asked her. “Yup,” she said.

All of this is to say: I don’t know. I don’t know if my independent school, or independent schools in general, are doing a good job of serving our students of color. When these students succeed–and they do–I don’t know how much of that is attributable to our serving them well and effectively and how much of it is the product of their use of those various kinds of capital as workarounds and compensatory measures. I don’t know how to find out if my colleagues sincerely believe that “those students” can aspire to and attain to the same things our other students do, or if there is a glass ceiling, an unacknowledged track, that designates them second-class school citizens.

I want to know. “Someone should study this!” I think to myself. Me? Or could an independent school like mine attempt a Participatory Action Research Project along the lines of the Council of Youth Research, in which “urban youth of color research educational conditions,” by “appropriat[ing] traditional research methods for critical uses and employ[ing] creative approaches to conveying research findings” in an effort to “transform inequitable learning conditions and structures” (Bautista et al., 2013, p. 2).

What if the students in our outreach program were invited to perform participatory action research in our school community? A summer session could initiate them in the methods and language of research and allow them to design research protocols. Over a school year, they could work (for credit) on their research protocols and perform site visits like the students in the Council of Youth Research. Perhaps a second summer session could bookend the experience and allow them to design and create their novel ways of sharing their research.

Is it wrong–ignorant, tone-deaf?–to appropriate this urban research project and apply it to a rich school environment that doesn’t face the same problems? I think not. There are certain unique researchable questions (problems?) presented by the starkly stratified environment of an expensive prep school committed to an outreach program like ours. These students need empowerment and understanding, and we are kidding ourselves if we think they are not made aware–daily–of institutional and cultural barriers and inequity. Perhaps the best people to investigate this question at my school are the people it affects most acutely.

References:

Bautista, M.A., Bertrand, M., Morrell, E., Scorza, D., & Matthews, C. (2013). Participatory action research and city youth : Methodological insights from the council of youth research UCLA, Teachers College Record, 115 (100303), 1–23.

Goldstein, D. (2014). Don’t help your kids with their homework. The Atlantic, April 2014. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/04/and-dont-help-your-kids-with-their-homework/358636/

Liou, D., Antrop-Gonzalez, R., & Cooper, R. (2009). Unveiling the promise of community cultural wealth to sustaining latino/a students’ college-going information networks. Educational Studies, 45, 534-555.

Ohikuare, J. When minority students attend elite private schools. The Atlantic, Dec. 2013. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2013/12/when-minority-students-attend-elite-private-schools/282416/

Project Excellence. (n.d.). In Phoenix Country Day School: Student Life. Retrieved June 2, 20014 from http://www.pcds.org/about-pcds/projectexcellence.

Rodriguez, R. (1982). Aria. Hunger of memory: The education of Richard Rodriguez. New York, New York: Bantam.

Thomas, M., Aletheiani, D., Carlson, D., & Ewbank, A. (2014). ‘Keeping up the good fight’: the said and unsaid in Flores V. Arizona. Policy Futures in Education, 12 (2), 242-261.

Valencia, R. (1997). The evolution of deficit thinking: Educational thought and practice. Oxfordshire: Routledge.