Strayhorn, T. (2008). How College Students’ Engagement Affects Personal and Social Learning Outcomes. Journal of College and Character, X(2), 1–16.

Summary

This article is presents possible interventions to influence student engagement, which then results in student learning. A widely accepted model for identifying change is presented. This model is called I-E-O and was developed by Astin in 1991. In the model, I represents “inputs”, E represents “Environment” and O represents “Outcome”. The model developed by Astin is considered a foundational model in evaluating the impact of planned interventions (or activities) with students. Through the use of data collected in the College Student Experiences Questionnaire (CSEQ, the researcher conducted quantitative analysis to identify potential activities (inputs) that would yield a measurable increase in student learning (outcome). The possible outcomes originated from the Council for the Advanced of Standards in Higher Education. Therefore, the research was attempting to determine appropriate input that would correlate to the desired CAS outcomes.

Literature Review

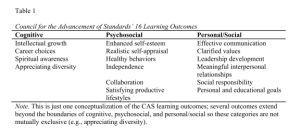

The literature review focused mainly on the frameworks for analysis, the I-E-O model and the standards identified for CAS. In accordance with the I-E-O model, student learning is the result of inputs and environment. The specific desired learning outcomes were identified from the CAS standards. See the table below in which the researcher categorized the standards based upon desired outcomes.

According to the researcher, the CAS standards are commonly agreed set of outcomes we hope for students that include categories related to developing effective communication practices, accepting diversity in thought and experience, forming meaningful relationships, and acquiring the ability to think critically. The researcher also defined student engagement as “’the time and energy that students devote to educationally purposeful activities and the extend to which the institution gets students to participate in activities that lead to student success’ (Kezar & Kinzie, 2006, p. 150)” (Strayhorn, 2008, pg. 6)

Quantitative Research

The research study is seeking to answer two research questions “(a) Is there a statistically significant relationship between students’ engagement in college experiences and personal/social learning gains and (b) What is the relationship between students’ engagement in college experiences and their self-reports personal/social learning gains, controlling for background differences” (Strayhorn, 2008, pg 2). The researcher is adding to the body of work based upon a possible gap in research in this field.

The CSEQ is administered by Indiana University Bloomington. It is typically used for assessment. It is comprised of 191 items “designed to measure the quality and quantity of students’ involvement in college activities and their use of college facilities” (Strayhorn, 2008, pg 4). It was administered to 8000 undergraduates attending 4-year institutions. The researcher used survey data used and identified certain questions thought to correlate to specific learning outcomes from CAS. Component factor analysis was used for the initial round of quantitative analysis. The next step was the incorporation of hierarchical linear regression. In hierarchical linear regression, variables are entered into the data set based up an order determined by the researcher.

Limitations of this research include a lack of detail about how participants in the survey were selected. Also, only 4-year institutions were selected. Community college students might have been included if they had transferred. However, that information was not provided. The initial review of the data can be replicated, since it is available. However, the researcher used assumptions to first, correlate what he perceived to be relevant data points along with the CAS standards and then second, to organize their analysis based upon a possible impact.

Implications and Future Research

Based upon the analysis, the researcher concluded that peers and active learning were found most impactful on student engagement. Therefore, programs should consider programs that bring students together and support learning such as peer study groups, peer mentors, social outreach. Since faculty provide the opportunities for active learning, this was further discussed in terms of possible research opportunities that faculty could provide to students. Strayhorn (2004) specifically suggests “programs should be (re-) designed for faculty and students to collaborate on research projects, co-teaching experiences, and service learning activities…” (pg. 11). Future research opportunities might be beneficial in showing how peer and faculty engagement opportunities do correlate to successful student outcomes. Strayhorn (2004) further clarifies this by stating “future research might attempt to measure the impact of engagement on other learning outcomes such as those identified by CAS including effective communication, appreciating diversity, and leadership development…” (pg. 12).

Another possible extension of this research is to incorporate the I-E-O model along with student development theories. Student development theories are theories advisors can use to understand how a student is maturing and growing (Williams, 2007). I mention this to suggest that a student’s phase of development could potentially be an influential factor in how the student responds to inputs and environments. This is a possible extension of this research and relates to my research field since I am beginning to explore outcomes related to advising interventions. This could include qualitative research alongside the quantitative research analysis. An example would be to conduct interviews to get a sense of whether the inputs suggested by this research lead to different levels of outcomes based upon the phase of the students’ development.

References

Williams, S. (2007). From Theory to Practice: The Application of Theories of Development to Academic Advising Philosophy and Practice. Retrieved from NACADA Clearinghouse of Academic Advising Resources Web site:

http://www.nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Clearinghouse/View-Articles/Applying-Theory-to-Advising-Practice.aspx