Hruby, G. G., & Goswami, U. (2011). Neuroscience and Reading: A Review for Reading Education Researchers. Reading Research Quarterly, 46(2), 156–172. doi:10.1598/RRQ.46.2.4

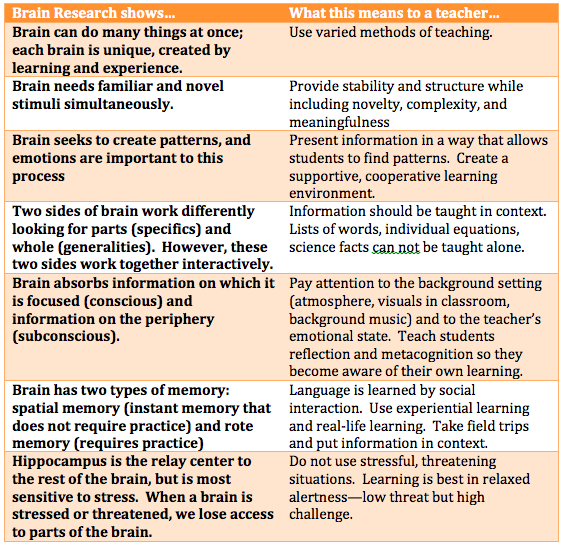

Research follows money. Where there is funding, researchers flourish and new information is discovered and disseminated. Funding many times is related to solve problems. Brain research is no different. Most brain research deals with abnormalities in brain functioning—dementia, Parkinson’s disease, post-traumatic stress syndrome, attention deficient disorder, and dyslexia to name a few. However, little has been done to explore the workings of a normal brain at work.

One area where this is less true is neuroscience and reading. Scientists are trying to uncover the secrets of the brain and language; language is what differentiates humans from other animals. Thus, a body of work has been created around the issue of reading.

Hruby and Goswami (2011) review a wide variety of research from the neuroscience field, specifically for researchers in reading education. Researchers are using imaging studies to find what parts of the brain are involved in reading, while others are studying neural activity to establish a detailed seconds-long timeline of what happens during the reading process.

Decoding

During decoding, brain areas related to hearing, vision, spatial processing and speaking are activated. In general, many of the reading functions take place on the left side of the brain. However, children younger than nine years of age use more of the right side of their brain than older children and adults. It is supposed that normal development accounts for this difference. Located on the left side of the brain is an area called the Visual Word Form Area (VWFA). When adults are shown printed words, this area shows activity. In children, more activity is seen in this area as they become better readers. Although this area is responsive to any sequence of printed letters, more activity occurs when the string is an actual word. The brain can distinguish a real word from a nonsense word in less than 1/5 of a second (the average is 170 milliseconds). In addition to the VWFA, other parts of the brain are dealing with the auditory functions of decoding (left occipitotemporal regions) and the combining of the auditory and visual functions (temporoparietal junction/TPJ).

When reading, children’s brains activate three core areas in sequence. In early reading instruction, it is assumed that students first pass through a stage where they identify whole words and their meaning (I equate this to sight words). If this is true, all three core areas are not needed to go from print to meaning. However, in one study, the children consistently used all three areas. With further study and replication, this finding may have implications for the way we teach early literacy.

Comprehension

Moving away from decoding, Hruby and Goswami (2011) move to comprehension, beginning with vocabulary learning. The most prominent study compared learning vocabulary in one of three ways: spelling and meaning; spelling and pronunciation; pronunciation and meaning. Later, they were asked to recognize the new words in other contexts. Brain activation was strongest for the words that had been learned by spelling and meaning. This could be important for vocabulary learning because the stronger the recognition, the more easily we can recognize it and begin to add related information.

Along with individual words, language comprehension deals with semantics and syntax. Semantics is the relation of words to each other; syntax is the grammar that creates well-formed sentences. Research has shown that these three parts of reading comprehension happen in different parts of the brain and in sequence. First, the brain activates to understand individual words, then the semantics, and last the syntax. The areas of the brain that handle semantic and syntactic processing develop uniquely in each person, depending on their differing experiences. Very little neuroscientific research has been done on a reader’s prior knowledge and how that effects his brain processing as he reads.

Strengths and Contributions

This article is well-organized, clearly laying out at the beginning what will be covered, and ordering the studies in a linear pattern that is easy to follow. Major studies that apply specifically to reading research and instruction were chosen, and they were interesting to learn about. The authors are brave souls, attempting to bridge a very wide chasm between neuroscience, with its inherent mystery and intimidating vocabulary, with researchers in the reading field. This is a daunting task, and they have approached their topic with integrity. While trying not to diminish the work of the scientists, I think they have left the material too difficult for readers from other fields to understand. Granted, I have not read much on this topic, but I had to read most of the study summaries multiple times, parsing each sentence in order to get a basic understanding. The material is still inaccessible to many who need to know what is happening in neuroscience that effects education.

Final Thoughts

Hruby and Goswami (2011) conclude with thoughts concerning the role of neuroscience research and reading research, with which I strongly concur and which reflects conversations in my doctoral classes at Arizona State University. Neuroscience is an exciting new area of research, which can enlighten classroom practices. But, it is not the only truth to be considered. Reading research, whether based on traditional psychology, behaviorialism, or simply what works in the classroom, are equally important. Each is a lens with which to see a portion of the truth. Truth is found in the intersection and compilation of all these practices and viewpoints.