Margolin, S.J., Driscoll, C., Toland, M.J., and Kegler, J.L. (2013). E-readers, computer screens, or paper: Does reading comprehension change across media platforms? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 27, 512-519.

I never thought it would happen to me. I am, and always have been, a bibliophile. I love books for the stories within their covers, sure, but I also love books as books. I love spines and endpapers and embossing and cover art and epigraphs and acknowledgements and author photos and notes on the type and and those ruffly cut edges on fine hardcover editions. I still have the copies of Jane Eyre and Pride and Prejudice that my older sister, the best reader I know, bought for me for my 10th birthday. Touching their faded covers, I can still summon how those books felt like the kid sister’s longed-for invitation to hang out with the big kids. One of my fondest sensory experiences is the squeak of the plastic library cover on a book giving way to yield the sweet, pulpy smell of paper.

I resisted the e-reader, I did. When people argued its merits, telling me I could bring 500 books on vacation with me, I turned up my nose. No, I scoffed, I love the ritual of selecting which book gets the privilege of hopping from bookshelf to suitcase; I love when I finish a book on vacation and so, stranded in Glenwood, Minnesota, with nothing to read, I go into that used bookstore and buy whatever they have that looks pretty good. This is how I ended up reading Geek Love by Katherine Dunn. If I’d brought 500 preselected books with me, that book would never have found me and thank God it did. And then it happened:

Reader, I bought an e-reader.

Truth be told, I’m on my second e-reader. My first was a Kindle, and a few years after I bought it, I upgraded to a Kindle Paperwhite. I don’t really know why I succumbed in the first place. When Amazon announced the Kindle in 2007, I got a good head of steam up about it and swore I’d never give in. I have thousands of books. And I have a hard time parting with them. Before and after I’ve read them, they remain, stacked and spilling from shelves and boxes, in every room of my house. But my affection for gadgetry must have won out, because in 2009 I told my husband that, gee, well, maybe, for my birthday, I guess, perhaps, I’d like to have a … Kindle? He was all too happy to oblige, because he was the one who’d moved all those thousands of books, box by heavy box, when we bought our first home together.

I was surprised to find that I loved the Kindle. I didn’t even need to warm up to it. It helps that the designers have paid attention to the tactile and sensual aspects of reading, so the thing feels like a book in my hands and I can “turn” the page either with a tap on the screen or with a swipe something like the swipe of a licked fingertip. I will say this: My Kindle is only for reading. Deep reading. Immersive reading. Longform reading. Book reading. I do not read magazines or periodicals on it (I read those on my iPad!). It does not have browser capability (again, iPad). Although it does have some interactive functions–for instance, I can hold my finger down on a word and be taken to a built-in dictionary for a definition–I don’t make frequent use of them. It also has functions to allow me to annotate, “highlight” or “clip” portions of text, but I use those infrequently, as well. Truth be told, I am not a heavy annotator in my pleasure reading, and I never have been. Much in the same way that the dog breeds I like best are the ones that are most like cats, I chose the e-reader that was as much like an analog reader–ahem, book–as possible. I deliberately selected the Kindle for the fact that it’s not backlit (like the iPad) and therefore doesn’t result in eye strain, headaches, or fatigue (for me). I also made a conscious choice not to get an e-reader with browser capability or the ability to watch movies (the Kindle Fire, for example).

There are, of course, pluses and minuses to the Kindle. I’m one of those people who can remember that a passage or image was on, say, the bottom half of a left-hand page about a third of the way through the book. With the Kindle, all the “pages” are oriented identically. It’s harder for me to find that passage or image that I remember. On the other hand, I can use the search function to locate a remembered word or phrase from the passage. (Another bonus: When I want to analyze recurring imagery on my own or with my students, I can, for example, search for all instances of relevant words: boat imagery, colors, whatever.) I believe I read more with my Kindle, because if I finish a book at the doctor’s office, I can immediately start another. In fact, I can immediately buy another. Downside: On the Kindle, I can’t tell how long a book is. I can’t tell when the portion in my right hand starts to weigh less than the portion in my left hand so I know to start rationing it more slowly to make it last. On the Kindle, books just up and end on me. And then I’m confronted with a rude-seeming invitation to rate the book I read (how crass!) or buy another book. Can we just cuddle for a few minutes? Geeze. Of course, sometimes it’s a good thing that I can’t tell how long a book is. With the Kindle, I don’t reject titles because they’re 700 pages long and I’m not sure I’ll have the time. I just dig in and keep plugging away. When I secretly wanted to read a trashy Jodi Picoult book but I didn’t want anyone to know, my Kindle kept my secret. On the other hand, thanks to the popularity of Kindles, Nooks, and other e-readers, I can no longer survey a waiting room or airplane to find out what book is the Cold Mountain of this year. I once met and fell in love with a man on a plane because he was carrying a copy of Raymond Carver’s Cathedral. Somehow, I doubt that “So. How about the battery life on that Kindle, eh?” would have, well, kindled the brief but beautiful romance that followed.

As a reader and a teacher, I have often wondered if the type and quality of reading I’m doing on my Kindle is comparable to the the type and quality of reading I always did (and sometimes still do) on paper. This question has increased relevance to me now, as my school has recently decided to “move away from printed copies of textbooks and towards a greater adoption of digital resources and eBooks” (J. Boehle, personal communication, February 28, 2014). To that end, “all students in grades 7-12 will be required to Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) to school starting in the fall of 2015” (J. Boehle, personal communication, May 29, 2014). We teachers received our school-issued iPads last week (bringing my household total of Apple devices (iPads, laptops, and iPods) to a slightly embarrassing 9. This doesn’t include the treasured Kindle or my husband’s PC computer. Incidentally, we are a household of two people and three cats. We have more computers than we do sentient beings).

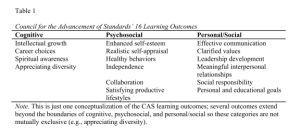

Reading “is a process that, once learned, allows an individual to mentally represent written text” (Margolin, Driscoll, Toland, & Kegler, 2013, p. 512). As simple as that sounds, reading is a cognitively complex act, and there are many theories about what exactly is going on when I curl up with an afghan, chew on the end of my ponytail, and get lost in Anna Karenina for the sixth time. Hoover and Gough (2000), operating on the Southwest Educational Development Laboratory’s (SEDL) framework of the cognitive foundations of reading, explain that “reading comprehension (or, simply, reading) … is based upon two equally important competencies. One is language comprehension–the ability to construct meaning from spoken representations of language; the second is decoding—the ability to recognize written representations of words” (p. 13). Furthermore, each of these two abilities depends on “a collection of interrelated cognitive elements that must be well developed to be successful at either comprehending language or decoding” (Wren, 2000, p. 20). Wren (2000) explains that, according to the SEDL framework, the elements that support language comprehension and decoding toward reading comprehension are as follows (p. 18):

- Background knowledge

- Linguistic knowledge

- Phonology

- Syntax

- Semantics

- Cipher knowledge

- Lexical knowledge

- Phoneme awareness

- Knowledge of the alphabetic principle

- Letter knowledge

- Concepts about print

Each of those elements could form the basis of a nuanced and lengthy exploration; for the purposes of this discussion, they serve only to underscore the cognitive complexity of reading. That is, we will take as a given that reading comprehension relies on an intricate set of brain tasks. The question before us is whether reading on a screen–specifically on an e-reader like a Kindle–as opposed to reading on good, old-fashioned paper, allows us to achieve that end goal: reading comprehension. That’s what Margolin, Driscoll, Toland, and Kegler (2013) examined.

So let’s take a look at their research protocol before we explore their findings (yes, I’m going to make you wait to find out whether you’re reading this as well on screen as you would if you were reading it on paper! It’s like another old favorite, There’s a Monster at the End of This Book) and what this means for my school, and my students, and me. The clearly written, error-free article is organized effectively, prefacing the study itself with a thorough review of the existing literature (see below) as well as the real-world applicability of the findings. The authors also firmly locate their study within a theoretical framework of reading, specifically the Construction Integration (CI) model (Margolin et al., 2013, p. 512).

Literature Review: The Holes in the Research

Memory, not Comprehension

Margolin et al. (2013) first established the research landscape on the subject of e-reading and observed a few trends that seemed to create a niche for their query. They observed that the previous research into electronic reading “has examined memory for text … [but] the reading literature has not yet examined comprehension” (Margolin et al., 2013, p. 512). That is, researchers have examined readers’ ability to recall what they read electronically, but not how well they understood it.

Process, not Product

Secondly, Margolin et al. (2013) established that the earliest research into electronic reading “focused primarily on the process and efficacy of reading from computers, rather than outcomes like comprehension and learning” (p. 513). For example, researchers studied the speed with which individuals could read and proofread on paper versus a computer (Margolin et al., 2013, p. 513) and analyzed discrepancies in terms of the experiential and physical differences between reading on screen and reading on paper (backlighting, typographic spacing and fonts, scrolling vs. page-turning, etc.) (Margolin et al., 2013, p. 513).

E-Readers, not Computers

Thirdly, Margolin et al. (2013) explain that previous research has focused on computer-screen reading with hyperlinks (blogs, online news websites, etc.) as opposed to e-reader reading, which more closely mimics book reading and doesn’t present opportunities for readers to click out of the text (p. 513).

Therefore, to fill the hole in the research presented by these established trends, Margolin et al. (2013) “looked to explore a new technology known as an e-reader, whose intended function is the singular process of reading, rather than searching for an evaluating information online” (p. 514). The authors argue that e-reader reading is fundamentally different from computer-screen reading because “there is no need to search or problem-solve to navigate through the hyperlinks, because these are not present on an e-reader device” like my Kindle (Margolin et al., 2013, p. 514). The authors make a very strong case for their study, demonstrating that the research to date has not really explored comprehension with e-readers. Their study is timely, given that e-readers are gaining in popularity among many age groups and contexts. In this manner, the authors make a compelling case for the relevance of this study to the field of cognition, educational psychology, and general reading.

Many schools, including my own, are implementing tablet or e-textbook programs. However, the authors fail to address that schools are, on the whole, implementing tablet programs, not e–reader programs. The value of this study is somewhat limited by the fact that e-readers are not the electronic device that is leading the way in the sea change that’s happening at schools. It’s the tablet–full of hyperlinks, browsers, and doodads–that is invading the classroom. So, even though the researchers used academic texts like the ones students study in school, this study may not ultimately be as germane to the burgeoning conversation surrounding how students read required texts in classrooms.

Data Collection Method and Research Design

Margolin et al. (2013) recruited 90 research participants ages 18 to 25 from an introduction to psychology course at a Western New York college (p. 514). Slightly less than a third of the participants were male, but the ratio of male to female participants was retained in the three different groups to which the participants were randomly assigned: Paper readers, computer readers, and e-readers (Margolin et al., 2013, p. 514). It is perhaps worth noting that none of the participants had any diagnosed learning disabilities or dyslexia (Margolin et al., 2013, p. 514). (I point that out simply because I’m particularly interested in how our switch to e-textbooks might affect–negatively or positively–our students with those issues. More on that a bit later.) Each of the groups was presented with 1o passages to read: five were expository, intended to “convey facts and information” (Margolin et al., 2013, p. 514), and five were narrative, intended to “tell a story or chronicle an event” (Margolin et al., 2013, p. 514). The researchers ensured that there was uniformity among the texts in terms of length and reading level, as measured by the Flesch-Kincaid grade-level scale (Margolin et al., 2013, p. 515). The participants were randomly assigned to one of three delivery methods: The paper readers read on standard 8.5″ x 11″ white paper, the computer readers read PDFs on screen, and the e-readers read on a Kindle with e-ink technology just like the one I have (Margolin et al., 2013, p. 515). Immediately following their reading of the texts, participants completed a questionnaire in which they answered analytical questions to probe their level of understanding and interpretation as well as questions about their process and experience (did they skip around, did they re-read, did they follow along with a finger, etc.) (Margolin et al., 2013, p. 515).

The organization of this study seems very thorough. While the researchers could have limited their exploration to correlation between media presentation (paper, computer, e-reader) and comprehension, they went a step further to examine the behaviors that readers employ to assist in their comprehension. This gives us a fuller picture of what reading looks like across all of these platforms and makes the conclusion more compelling.

Results and Analysis

The results portion of this article was less clear than some of the other components. More tables or graphs would have been helpful, especially in terms of depicting the relationships among media type, reading behavior, and comprehension. Nevertheless, a few takeaways were immediately apparent. For one, comprehension was found to be slightly lower for narrative passages than for expository passages overall, regardless of how the text was presented (Margolin et al., 2013,p. 516). The comprehension scores for all three presentation styles were comparable and reflected a similar (small) disparity between comprehension of narrative texts and expository texts (Margolin et al., 2013,p. 516). Comprehension was found to be higher for computer readers when they followed along with a finger or silently mouthed what they were reading; however, these behaviors did not improve comprehension for paper readers or e-readers (Margolin et al., 2013,p. 516). Examining each presentation of text on its own, reading behaviors for the most part did not make a difference in the reader’s comprehension of narrative versus expository text (Margolin et al., 2013, p. 516). The only two behaviors that seemed to correlate to significantly higher comprehension were finger-tracking and mouthing (Margolin et al., 2013,p. 516). There did not seem to be any difference in the frequency with which readers relied on most behaviors (highlighting, finger tracking, mouthing, taking notes, saying words aloud) across the three presentation styles, with one exception: When it came to skipping around while reading, the Kindle readers were found to do much less of this behavior than either paper or computer readers (Margolin et al., 2013,p. 516).

The authors acknowledge that the relevance and applicability of their study may be limited somewhat by the relative youth of the study participants. Older readers, who may have issues with working memory, may find that they encounter more reading comprehension problems overall or that the platform of delivery of text does make a difference in their comprehension. The study would have to be replicated with an older demographic before we could whole-heartedly say that reading comprehension isn’t negatively affected by delivery medium. The college students who participated in this study are probably very comfortable with technology by virtue of their age; it could be that we are seeing that reading comprehension is not negatively affected by e-reading as long as the e-reader has met a threshold level of comfort with the technology. It would also be interesting to study young, budding readers across these delivery methods to find out if the way we learn to read is affected by the medium in which we read. This study included people who were proficient readers and proficient users of technology; it might be telling to examine groups on either side of that center swath: young students with less reading proficiency and older readers with less technological comfort and less ideal working memories.

Discussion/Findings

The results of this study appear to be encouraging in a world where “the amount of digital text being created grows exponentially every day” (Margolin et al., 2013, p. 512) and where “reading, and more importantly, comprehension, is a fundamental skill necessary for the successful completion of almost any type of class as well as in the job marketplace” (Margolin et al., 2013, p. 512). Overall, the authors found no significant difference in reading comprehension among the paper readers, the computer readers, and the e-readers. Furthermore, while readers from all groups comprehended narrative texts slightly less well than they did expository texts, this difference was no greater for the computer-readers or e-readers than for the paper readers, suggesting that, narrative reading might simply be more difficult (for people of this age group and experience level) than expository reading. The data also suggest that people engage largely similar behaviors when reading on various platforms, that only finger-tracking and mouthing had any effect on comprehension (across all presentation styles), and that even that effect was minimal. In conclusion, Margolin et al. (2013) argue that “electronic forms of text presentation (both computer and e-reader) may be just as viable a format as paper presentation for both narrative and expository texts” (p. 517).

This is encouraging news for me personally and professionally, and it seems to support what my own “anecdata” has suggested: For me, reading on my Kindle really doesn’t feel any different from reading a book. I still cry in public with alarming regularity. In my role as a teacher, I have always had a policy of allowing my students to read in whatever platform or media they prefer (except smartphones), as I philosophically don’t believe in impeding reading. Reading is so personal, so… sensual … that I cannot bring myself to say to my students, who have 10 or more years of experience as readers, “No, don’t do it that way, do it this way.”

This study makes me feel somewhat better about the decision my school has made to move all of students’ instructional materials and textbooks to a single device–that is, if we can control the potentially distracting functions of their tablets and, in essence, turn them into e-readers. The benefits of such a policy are many. For one, having every text on an e-reader would mean that the days of schlepping a backpack so laden with books that it causes serious pain and even injury are behind us. I believe we have a responsibility as educators to look out for the physical well-being of our students, and sending a 100-pound kid home with 60-pound backpack doesn’t seem right to me. I’m also particularly attuned to the needs of our kids with physical disabilities, however rare they might be. I was a teenager with arthritis, and my school accommodated me by issuing me two sets of textbooks: One for my locker, and one for home use. But that didn’t help on the days when even lugging my U.S. history text to class was painful. And imagine the flexibility for me and my students when it’s discovered that we have an extra 20 minutes in class that we didn’t plan for and we can shift gears to a new essay or poem without everyone running to lockers and back!

What Next?

E-readers vs. tablets? What about phones?

However, the study raises several questions worth further investigation: are there any differences in reading comprehension or supportive reading behaviors when one compares Kindle reading to, say, iPad reading? I absolutely do not–could not–read a book on my iPad. I do read magazines and newspapers on my iPad, and while I think my taste in magazines isn’t exactly vapid (Smithsonian, The New Yorker, The Atlantic, etc.), this is grazing reading–I do it for shorter amounts of time and I allow myself to pursue tangents and offshoots at will). But for immersive, hours-long reading sessions, the backlighting on the iPad would wear out my eyes in an hour. Secondly, the iPad is loaded with bells and whistles that threaten to distract even the most devoted reader. The whole point of an iPad–and the reason my school is shifting to them–is that everything is right there in one place: Everything for good (books for every course all at one’s fingertips, no running to lockers or bemoaning books forgotten at home!) and everything for bad (E-mail! Text messaging! Facebook! Canvas! Photos! A camera! Shazam! The Internet!).

I’d like to see a study that explores e-readers as compared with these all-in-one tablets. Furthermore, I’ve had more than one student ask about reading our required texts on a smartphone. The constrained size of the screen, in addition to the aforementioned concerns about the iPad, compel me to reject that proposition out of hand. But what if research shows that reading on a 6.7-square-inch phone is just as good?

Students with learning disabilities or ADD?

Secondly, I’d really like to see an examination of how reading comprehension and reading behaviors are affected when the readers are using electronic devices and when the readers have attention deficit disorder, dyslexia, or other learning disabilities. As I’ve mentioned previously, we have a significant population of students at our school with these issues, and I’d hate to think we’re introducing a technology that makes school all the harder for them. As Margolin et al. (2013) point out, when a reader is distracted, his or her “capacity for processing text may be reduced, making difficulties with fully understanding the text more likely” (p. 512). How cruel to mandate that a kid with ADD arm himself with a weapon to sabotage his own performance.

What if kids want to go old-school?

I think it’s important to remember that this study suggests that there is no difference in reading comprehension among the three platforms. The obvious interpretation of that is that e-reading isn’t worse than traditional paper reading. But the inverse is suggested, too: when it comes to comprehension, e-reading also isn’t better than paper reading. Whatever the benefits of a tablet policy, they are likely associated with convenience and synchrony among students, as opposed to cognitive or pedagogical benefit (at least as far as reading is concerned). So what will I do in two years when a student says, “Is it OK if I read The Metamorphosis in this first-edition, hardcover edition that belonged to my grandmother instead of on my iPad?” My inclination will be to say the equivalent of what I say now to students who want to bring an e-reader instead of a hard copy of The Metamorphosis: “Sure, yes, whatever you like. Just make sure you have it every day when we need it in class.” But if my school is making this institutional change across the board, will I have the freedom and backing to say that? Or will I have to say, “No, please, I’d prefer you download it on the iPad.” That feels wrong to me. It feels wrong to interfere with a young adult’s established preference for reading medium given that there doesn’t appear to be a comprehension benefit.

That other “R”: Writing?

Of course, any exploration of how the cognitive experience of reading on screen differs (or doesn’t) from the experience of reading on paper invites me to think about reading’s dance partner, writing. How does student writing differ when it’s typed versus when it’s handwritten? I do know that research is ongoing in this area, and I’d like to explore it. Nowadays, a student can draft, revise, submit, and receive feedback on a “paper” without touching any actual paper.

Ultimately, though, this study seems to be a bracing splash of cold water for those educators, parents, and students who assume that reading on a device must be worse than reading in a book. This is a status quo bias and it’s not, in itself, a good reason to eschew new technologies that indubitably have benefits (convenience and allure, to name two). Some research into e-reading suggests that “reading online may be at the very least more complex than reading traditional printed text” (Margolin et al., 2013, p. 513) and that it involves “more than simply understanding what is encountered” (Margolin et al., 2013, p. 513), requiring “that the reader engage in other higher level processing of the material beyond creating a mental representation of the text” (Margolin et al., 2013, p. 513).

It’s so easy to make the mistake of thinking that the practices, habits, values, and institutions we have now are older and more established than they are. When it comes to reading, it’s perhaps useful to remember that “we were never born to read. Human beings invented reading only a few thousand years ago. And with this invention, we rearranged the very organization of our brain, which in turn expanded the ways we were able to think, which altered the intellectual evolution of our species” (Wolf, 2007, p. 3). We live in a time when innovation and invention take place at a mind-dizzying pace. It might behoove us to recall how we humans have adapted to our own inventions in the past. As Wolf (2007) argues, “reading is one of the single most remarkable inventions in history … Our ancestors’ invention could come about only because of the human brain’s extraordinary ability to make new connections among its existing structures, a process made possible by the brain’s ability to be shaped by experience” (p. 3).

As Winston Churchill said, “We shape our buildings. Thereafter, they shape us.”

References

Hoover, W.A., and Gough, P.B. (2000). The reading acquisition framework: an overview. In The cognitive foundations of learning to read: A framework. Retrieved from Southwest Educational Development Laboratory Web site: http://www.sedl.org/reading/framework/framework.pdf

Margolin, S. J., Driscoll, C., Toland, M. J., & Kegler, J. L. (2013). E-readers, computer screens, or paper: Does reading comprehension change across media platforms? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 27(4), 512–519. doi:10.1002/acp.2930

Wolf, M. (2007). Proust and the squid: The story and science of the reading brain. New York, NY: Harper.

Wren, S. (2000). The cognitive foundations of learning to read: A framework. Retrieved from Southwest Educational Development Laboratory Web site: http://www.sedl.org/reading/framework/framework.pdf