Vidali, A. (2007). Texts of our institutional lives: Performing the rhetorical freak show : Disability, student writing, and college admissions. College English, 69(6), 615–641.

This is how I picked a college: My junior year of high school, a big alphabetical book of Colleges in the USA mysteriously appeared in my bedroom, the bedroom in the house I’d lived in since I was three months old. I thumbed through the big book of colleges and, I like to joke now, I got through the A’s. I attended Arizona State University.

Of course, I applied to a few other schools (six, which was in line with national averages but nowhere near the 10, 12, or 15 that some of my students submit nowadays), and I got in to all of them. It’s fun to ponder who or what I would be now, 20 years later, if I’d attended the University of Colorado at Boulder. Would I own Birkenstocks? What if I’d gone to the University of Central Florida, where I was offered a scholarship? Would I be tan? The University of Arizona, the University of South Florida ,the University of Utah, University of Maryland (though I had no intention of staying so close to home or going to the school one of my brothers had attended)? Would I be any different now, or would I just have a different collection of T-shirts and beer coozies?

Unlike so many of my students at the expensive, prestigious private school where I now teach, I didn’t really care where I went to college. I knew I wanted to go to a big school far away from home. I wanted to meet a thousand new people and have teachers none of my three older siblings had had before me. I wanted to major in music. I wanted to flee. I used the compass that had gotten me through geometry to draw a circle on a map of the USA, with Washington, D.C. at its center and a radius of 1,500 miles. Anything within the circle was a no; anything outside the circle was fine with me, especially if they had low admissions standards (I was suffering from burnout, low self-esteem, and simmering anxiety at the time).

I sent in my applications, I recorded my auditions for the music schools, and I awaited the fabled big envelope. I did not write any essays, personal statements, or statements of purpose. If I had been asked to write these things, I would have been confronted with a big decision: do I reveal to the people reading the essay, the people with my fate in their hands, that I have a physical disability–namely, severe rheumatoid arthritis? There would be advantages, of course: a narrative angle that distinguished me from the masses of similar-seeming applicants, for one. But there would be a big risk, too. Would my disability, which wasn’t reflected or revealed in any other element of my application, work against me? Would the admissions people doubt my suitability for sustained academic work? Would they peg me as a dropout risk?

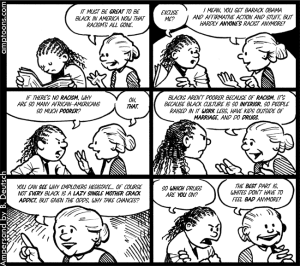

In “Texts of our institutional lives: Performing the rhetorical freak show : Disability, student writing, and college admissions,” Amy Vidali (2007) argues that “institutional writing”–of which these college entrance essays are a type–pose risk for all students, but particular risk for students with disabilities. According to Vidali, students who choose to write about their experiences with disability for their college entrance essays are, in effect, participating in the same push-pull of power that participants in freak shows did. Students are are acting out of necessity, Vidali argues, as they “would not write these admissions essays if they didn’t have to, and freak-show performers would likely have worked other jobs had gainful employment been available to them” (2007, p. 625). Furthermore, students find themselves in an “unequal rhetorical negotiation … where one person performs while others judge … similar to the relationship between freak-show performers and the objectifying gaze of spectators” (2007, p. 625). In short, students who write about their disabilities on these kinds of essays must be willing to “risk discrimination and create a ‘rhetorical spectacle’ of disability if it increases the chances of ‘getting in'” (Vidali, 2007, p. 623).

For her study, Vidali examined undergraduate students’ application files (after they’d been admitted to and begun attending college). She examined the rhetorical devices, structures, and tropes these students used in writing their experience of disability, and then she interviewed them to better understand their intentions, strategy, and reservations about doing so (if any). In the case study presented here, Vidali examines the essays and interviews with three subjects, all of them white, English-speaking women of “typical college age” (2007, p. 617). Though the larger pool of subjects included students with “vision impairments, brain injuries, cerebral palsy, and repetitive stress injuries, as well as students who are hard of hearing” (Vidali, 2007, p. 617), the three women who constitute this case study all have learning disabilities.

It is crucial to point out that Vidali comes at her study operating on the sociological model of disability, as opposed to the medical model, and therefore “conceive[s] of disability as a social and political identity rather than as a pathological condition, individual burden, or personal tragedy” (Linton qtd. in Vidali, 2007, p. 617).

Some really interesting commonalities emerge from Vidali’s examination of these women’s essays, commonalities that the author argues derive from the limited ways disability is framed and talked about in the larger culture. For example, two of the three employed a “three-part structure, moving from humiliation to a moment of change to overcoming disability-related obstacles” (Vidali, 2007, p. 672). Anyone who’s seen any movie featuring a disabled character will recognize this arc: disabled people are often depicted as being shamed, humiliated, or depressed until the magical moment when, after persevering nobly, they have their wishes granted (often by an able-bodied physician acting as fairy godmother) and overcome the obstacle presented by their disability. Likewise, these two students emphasized having overcome their disabilities. Their essays have “happy endings” (Vidali, 2007, p. 627). Furthermore, they write in terms of old selves and new selves, echoing another classic aspect of the rhetoric of disability, as expressed by Kristin Lindgren: “illness represents not only a crisis in the body but also a crisis in identity” (qtd. in Vidali, 2007, p. 626).

The third woman in the case study did not rely on the three-part structure, nor did she provide a happy ending. She did not write about old selves and new selves or transcending or overcoming her disability. In fact, this third writer eschewed personal details of her disability narrative altogether, opting instead for a discussion of “equal opportunity for people with learning disabilities” and “the politics of disability disclosure” (Vidali, 2007, p. 627). This student-author writes in an assertive voice, even slipping into second person to challenge the reader (a college admissions professional, the holder of power, the person who paid admission to this freak show) in a series of questions. Vidali calls this decision daring and even suggests that it’s somewhat subversive: she is bucking “the traditional representation of disability as personal and the strict confines of the admissions essay–which compel that all successes be solely the result of individual effort” (Vidali, 2007, p. 626).

One thing that all three student-authors had in common was the desire to stand out. This isn’t surprising; the students I teach have been hearing since fifth grade how important it is that their college applications make them seem unusual, unique, well-rounded, multi-faceted, different from the others. Nowadays, it seems, “standing out” isn’t even enough! Vidali quotes from Rachel Toor’s Admissions Confidential: “Many schools are looking for what they call ‘angular’ kids, those with a much more focused interest or talent,” (qtd. in Vidali, 2007, p. 630), kids she calls “BWRKs,” which is “admissionese for bright well-rounded kids” (Toor qtd. in Vidali, 2007, p. 631). The necessity of “standing out” is particularly interesting in the context of young adolescents with disabilities who, if my own experience is a reliable indication, spend a great deal of time expressly trying not to stand out. Particularly for students with intellectual or learning disabilities, for whom their difference has most likely been treated as a deficit in the context of school, it must be something of a relief, if not a trip to bizarro-world, to encounter this writing assignment where, suddenly, they have an “angle” other students lack. They stand to gain from the exhibition of their disability just as a bearded lady or a pair of conjoined twins did by joining one of P.T. Barnum’s traveling troupes of freaks and oddities. When you’ve been marginalized, and an opportunity comes to get paid for your marginalization, it’s hard not to jump–or limp–at it.

But benefiting from one’s marginalized status is not an uncomplicated decision, especially given a culture that is suspicious of disabled people and all too eager to accuse disabled people of inflating, exaggerating, or even making up their disabilities. In fact, one of the student-authors here begged Vidali not to include a comment she’d made in the interview about manipulating her application. Vidali writes that the author “sensed that she was not supposed to admit that her discussion of her disability in her admissions essay was anything other than a pure distillation of her disability experience … admitting her disclosure is a managed performance pulls the curtain back too far” (2007, p. 632).

Another potential pitfall of attempting to write about disability on an application essay is the mismatch between the conventions of the genre and the nature of disability. These are short, pithy writings, and chronic disability is by definition not short and is rarely pithy. “This isn’t the winning touchdown, the cultural awareness gained on a trip to Mexico, or even the insight from experiencing a moment of racial discrimination”–all popular topics for student essays–and the writer “cannot place her disability in the past or check off a box labeled ‘lesson learned,’ because the extraordinary scholastic needs that result from her disability are past, present, and future” (Vidali, 2007, p. 616).

Vidali argues that “reconsidering the ambiguous agency of the freak in a circus setting provides an important opportunity to rethink the idea of students (with and without disabilities) as mere rhetorical dupes of an impressive admissions system” (2007, p. 616). This is no small thing, given that, according to Vidali, “9 percent of all students in postsecondary education have disabilities and because the consideration of disability urges attention to the diversity of all students” (2007, p. 617).

The purpose of Vidali’s study wasn’t to examine the effect of divulging disability on an applicants’ acceptance, though that would be a fascinating onion to peel: As schools develop public statements of diversity, is the climate changing such that it becomes increasingly advantageous to reveal a disability? While according to the rules admissions committees may not be able to factor in a student’s disability, admissions committees are made up of people with intricate identities, biases, and values just waiting to be plucked by the right story from the right student at the right moment. I’d also like to know more about the rhetorical styles and features student-writers with non-intellectual disabilities employ: is a student who suffered a paralyzing accident also likely to use the three-part structure? How do students write about depression and anxiety, which rarely are conquered but rather accommodated? What about eating disorders? How far does the category of disability extend: Could/should a student write about recovery from drugs or alcohol and expect to “stand out” in the right ways? When does the risk outweigh the reward? Which kinds of freaks are going to be most successful?

Vidali argues first that the field of disability studies–and its associated lexicons, rhetorics, and models–needs to be brought to the forefront of discussions of composition and language. She argues that teachers tend to discuss disability with their students, if they do so at all, from medical and psychoanalytic models as opposed to the postmodern identity-making models they use to discuss race or class (Vidali, 2007, p. 618). The secondary English classroom, which in my world is a training ground for the rhetoric and composition classroom these students will graduate to, already examines “‘how language both reflects and supports notions of the Other'” (Brueggemann qtd. in Vidali, 2007, p. 618), “challenges false binaries, and connects issues of practice and theory” (Vidali, 2007, p. 618) and so a significant and purposeful discussion of disability in these contexts would be natural and appropriate. Vidali is not in the business of critiquing these student essays; rather, she is preoccupied with “analyzing and locating the power dynamics and inequities that admissions essays both produce and reproduce” (2007, p. 622).

I am interested in these things, too. I’m also interested in helping students more successfully navigate the demands of these personal statements as part of their college application processes. To me, these essays are problematic partly because they ask students to write personally, revealingly, and profoundly about themselves when many of them have spent 12 years being trained to believe that first-person writing is unacademic, unimportant, unprofessional, and unwelcome. I think we need to do a better job in general teaching students how to write about themselves without navel-gazing or resorting to derivative, trite cliches.

After reading this article, I think the mandate to do so is especially necessary for our students with disabilities. We need to teach them how to write about their disabilities in ways that aren’t limited to these Hollywood-sanctioned story arcs. If we want them to be empowered by and unapologetic about their manipulation of rhetorical tropes, if we want to give them narrative control of their stories, we need to help them discover what those tropes are. We need to clue them in to the power dynamic that is the context of ability/disability in the world they live in. To do so, we need to include disability studies in our curriculum the way we do studies of race, gender, and class. Though the benefit of this inclusive curriculum would be strong for students with disabilities, it would also be good for students who don’t identify as disabled, just in the way that exposing and analyzing racism benefits both minority and majority students.

As a working professional, I know the treacherous legal complications of divulging disability at a job interview. The freak show push-pull dynamic is present in that context, too–but, I would argue, the potential gains are smaller than in the college admissions process. Hirers are considering the drain you’ll pose on their health plan, how many days of work you’ll miss, and whether you’re a liability for a discrimination lawsuit. Of course, all of that could change if we increase the visibility of disability as an axis of social identity.

If I’d been asked to write an essay to get into college 20 years ago, I don’t know if I would have written about my arthritis. But perhaps it’s very telling that when, less than a year ago, I was asked to write a personal statement for admission to this very doctoral program, I consciously redacted my writing for any direct mention or allusion to my disability. I split the difference, though–the writing sample I submitted along with my personal statement scrubbed clean of arthritis was a published essay in which I made explicit reference to my chronic illness. I’m 37 and confused and ambivalent about how much to say, how much to protect. I can only imagine what my 18-year-old students feel.

Teenagers know well what it is to feel like freaks, especially students with any kind of difference. Perhaps we need to educate them better about the complexities–the risks and the rewards, the empowerment and the objectification–of the freak show and then let them decide what kind of performance they want to put on.

References

Brueggemann, B. J., White, L. F., Dunn, P.A., Heifferon, B.A., & Johnson, C. (2001). Becoming visible: Lessons in disability. College Composition and Communication, 52(3), 368–398. doi:10.2307/358624

Lindgren, K. “Bodies in trouble: Identity, embodiment, and disability.” Gendering Disability. Ed. Bonnie G. Smith and Beth Hutchinson. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2004. 145-65.

Linton, S. Claiming disability: knowledge and identity. New York: New York UP, 1998.

Toor, R. Admissions confidential: An insider’s account of the elite college selection process. New York: St. Martin’s, 2004.